As Graham Robb put it, “readers of poètes maudits often identify with the poets themselves, [whereas] critics and biographers tend to identify with the parents.” Like Robb’s biography of Rimbaud, Faas’s Robert Creeley counts among the rare exceptions to this rule. As Eric Miller writes: “Out of an unsavoury pulp of booze, bruises and tears arose Robert Creeley’s admirable poems. Faas plausibly prefers the work Creeley wrote before he was institutionalized, that is, in the bland – rather than psychiatric – sense. Faas’s discussion of the poet’s later work is somewhat cursory, somewhat mocking; perhaps the intended effect of such mockery is to revive the fire in the indignant ageing poet. Derision as a stimulus to growth occasionally works … Ekbert Faas’s account of Creeley’s life is immensely readable, phrased in something of the accelerated, demotic style – half scholarly, half journalistic – practised by Greil Marcus in Lipstick Traces. Under the transient influence of this racy style, the reader may miss a time when university programmes did not entirely throttle the world of imaginative writing.” (Canadian Review of Books, 31, 2, 2002, 20-22)

As Graham Robb put it, “readers of poètes maudits often identify with the poets themselves, [whereas] critics and biographers tend to identify with the parents.” Like Robb’s biography of Rimbaud, Faas’s Robert Creeley counts among the rare exceptions to this rule. As Eric Miller writes: “Out of an unsavoury pulp of booze, bruises and tears arose Robert Creeley’s admirable poems. Faas plausibly prefers the work Creeley wrote before he was institutionalized, that is, in the bland – rather than psychiatric – sense. Faas’s discussion of the poet’s later work is somewhat cursory, somewhat mocking; perhaps the intended effect of such mockery is to revive the fire in the indignant ageing poet. Derision as a stimulus to growth occasionally works … Ekbert Faas’s account of Creeley’s life is immensely readable, phrased in something of the accelerated, demotic style – half scholarly, half journalistic – practised by Greil Marcus in Lipstick Traces. Under the transient influence of this racy style, the reader may miss a time when university programmes did not entirely throttle the world of imaginative writing.” (Canadian Review of Books, 31, 2, 2002, 20-22)

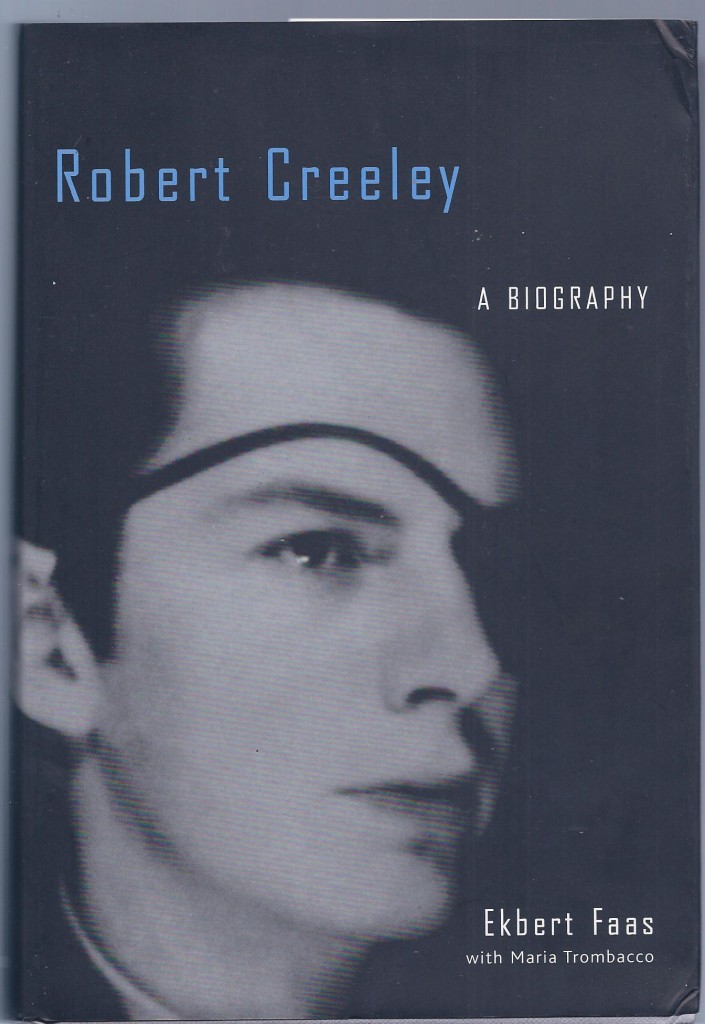

“Ekbert Faas, one of the foremost scholars of contemporary American poetry, began working on this biography 20 years ago, when Creeley authorized the project … In it, he focuses on Creeley’s first 40 years, utilizing interviews with and writings by Creeley’s friends and associates, especially the journals and memories of Creeley’s first wife, Ann McKinnon.” (Globe and Mail, October 27, 2001, 23)

“Briefly stated, Faas admires the younger Robert Creeley for the raw-edged, nerve-screeching quality of his life and work, but he has little respect for what he became from the early 1960s forward, once fame and money were his for the taking … Faas gives a credible portrait of the artist and those closest to him.” (Mark Melnicove, “A Life Half Told,” Ruminator Review, Winter 2001-2002, 55)

“Ekbert Faas has chosen an audacious style for the first biography of one of the greatest American poets … Faas mimics Creeley’s language and his rhetorical shifts, often to hallucinatory effect. The biography’s appendix, which consists of the reminiscences of Ann MacKinnon, Creeley’s first wife, heightens this effect, for in important particulars her view does not square with that of his letters. Still, if Faas is correct, the facts are disturbing, whatever they are … the biography is mesmerizing.” (David Andrews, Review of Contemporary Fiction, 22, 2, 2005, 250)

“In this biography, the biographer turns into the biographee, ‘impersonating voices, senses of humour, ironies, sarcasms, hypocrisies.’ The result is remarkable, and one easily forgets that Faas’s intense book is in fact based on a rather simple and familiar premise – namely that, at least in the case of the poet, a wild life generates better works. Le style est l’homme même, and the nicer the man the duller the poetry. For Faas, the philandering, boozing, drug-abusing and wife-beating Creeley, while personally none too appealing, was a more interesting writer than the older, wiser but also wearier sage mumbling ‘post middle-age’ platitudes about life and death … Such ventriloquizing is not limited to the book’s protagonist; Faas easily slips into the minds, or holds the pens, of Creeley’s friends and disciples (‘How would a man whose writing could cause such turmoil in your brain affect you in person?’) and troubled wives (‘Would she have to give him shots?’) … I enjoyed this book, as I would a well-written novel, realizing at the same time that Robert Creeley, in method and intent, takes us back to the olden days, when anxious biographers stayed clear of any discussions of their subject’s works while literary critics, as Walter Jackson Bate once lamented, shrank from ‘the rich and embarrassing complexities of what it meant to be a living person.’” (Christoph Irmscher, “Lovely Damn Things,” Canadian Literature, 180, Spring 2004, 129-30)

“This is the first book-length biography of one of the world’s preeminent poets, covering the first 40 years of his life … well-written, well-researched.” (L. Berk, Choice, 39, 8, 2002)

“Ekbert Faas, the author of this new biography, had earlier edited Creeley’s correspondence with the Canadian poet Irving Layton, as well as an anthology of essays and interviews … in which Creeley plays a prominent part.” (Marjorie Perloff, “A Survivor,” Times Literary Supplement, April 26 2002, 5-6).

Also see E. Faas’s reply, particularly to Professor Perloff’s claim, that he gave a “lurid portrait of the artist”: “Personally, I couldn’t think of a higher tribute to the younger poet than my comparing him to Rimbaud. But if I’d guessed that anyone might glumly misconstrue my upbeat portrait of him to this effect into that of a ‘drunk, a heavy drug-user and a reckless womanizer,’ I might have added that his so-called ‘iniquities’ along these lines strike me as rather dilettantish at worst. Also, there was no need for my allegedly scurrying around in search of ‘new and spicy bits’ for my ‘lurid portrait.’ Plenty of such ‘bits,’ which we deliberately suppressed, remain in my possession.” (TLS, June 7, 2002, 17)

“Creeley must be valued for his poetry – or scrapped for it. I confess that at the time of For Love (1962) and Words (1967) I had a high regard for him as the heir to William Carlos Williams’s minimalist aesthetic and the author of such zeitgeistful poems as “The Dishonest Mailmen” … But rereading Creeley’s poetry in connection with Faas’s biography I have become skeptical. I begin to think that the ones who benefit most from a policy of scrupulous minimalism are those who don’t know how to decorate: Paint the walls white, strip the floor, furnish the bare space with futons and pine-plank bookcases – and maintain an enigmatic silence by which one may come in time to have a reputation for depth.” (Thomas M. Disch, “Creeley in His Time,” Weekly Standard, 7, 8, 2001, 34-36)

“The angriest bohemian, who nurtured so many avant-garde careers with his small magazines while pulling The Island and For Love out of his bag of tricks, gets unvarnished but admiring treatment here … Despite late-career reservations, the account of Creeley’s first 40 years embraces the writer like a comfortable old jacket, and this biography feels a good fit.” (Kirkus Book Reviews, Nov. 2001)

“Returning to Robert Creeley’s work, with Ekbert Faas’s extraordinary biography, I am struck not only by the limitations the poet has imposed on himself, but also by how distinctly he now seems to belong to a particular cultural moment, in which stress was laid on ‘process’ in art, as often as not as a substitute for content … fascinating.” (James Campbell, “Was That a Real Poem?,” Threepenny Review, 90, Summer 2002, 15-16)